To deliver on President Trump’s campaign promise to deport millions of people, his administration is pushing new approaches to immigration enforcement across much of the government.

Officials have closed the border to asylum-seekers. They have unleashed immigration officers, often wearing masks, to make arrests on city streets. They have revoked legal status from recent arrivals. They have built new tent camps and re-opened prisons to hold immigrant detainees. They have pushed foreign leaders to accept deportees and local officials to allow ICE agents into their facilities and databases.

As the crackdown progresses and the border remains essentially closed, both the people targeted for deportation and their journeys through the system now look very different, a New York Times analysis of government data shows.

Most people who were deported during President Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s administration were among the millions of recent arrivals arrested at the border. They were detained and quickly deported through a process called expedited removal.

As border crossings dried up, Mr. Trump lifted restrictions on whom immigration officers could target elsewhere in the country. More deportees are now drawn from this wider pool. People are typically held in detention until they can be removed, and far fewer people are released.

The data, which includes every arrest, detention stay and deportation conducted by ICE, was obtained through a lawsuit and made available by the Deportation Data Project, an academic group.

It shows in great detail the impacts of Mr. Trump’s policies, including which communities have been most affected and the sometimes complicated paths people must travel as the government tries to remove them.

Many of the people ICE is now targeting entered legally in recent years under special programs created by Mr. Biden. Mr. Trump canceled those programs and has tried to revoke the legal status of their participants.

Where ICE makes arrests

The Trump administration has said it would prioritize deporting the “worst of the worst criminal illegal aliens.”

Historically, ICE detained immigrants who had committed crimes through “custodial” arrests — picking up people who had already been arrested by other law enforcement agencies from jails and prisons.

While custodial arrests still make up half of all immigration arrests, ICE has increasingly gone after anyone who may be in the country illegally, whether they have a criminal record or not.

Most ICE arrests at jails and prisons take place in Republican-led states like Florida, Georgia and Texas.

The rest are “at-large” , which are more common in states led by Democrats, like California and New York, where many local agencies do not cooperate with ICE.

More people who have been in the country for years or decades are being swept up and removed. More than 3,000 adults who entered before the age of 16 — potential “Dreamers” — have been deported, as have more than 4,000 children.

Where they are held

In the past, most people who were arrested were released to await their day in immigration court. Illegal immigration is a civil — not a criminal — offense, and detention was designed to hold only those deemed a flight risk.

But the Trump administration told ICE to hold people indefinitely and told immigration judges that most people are no longer eligible for bail. The Laken Riley Act, passed in January, further narrowed who can be released.

Immigrant detention centers are filling up, even as the Trump administration has opened dozens of new facilities to expand the capacity and reach of this network.

The detained population has nearly doubled, to more than 68,000 people in December, an all-time high.

People detained by ICE have described unsanitary and unsafe conditions in some detention centers — including rotten food, a lack of access to showers and toilets, and the use of solitary confinement. At least 32 people have died in ICE custody since Mr. Trump took office, more than the number in Mr. Biden’s entire four years in office.

Officials have denied claims of poor conditions and mistreatment of detainees.

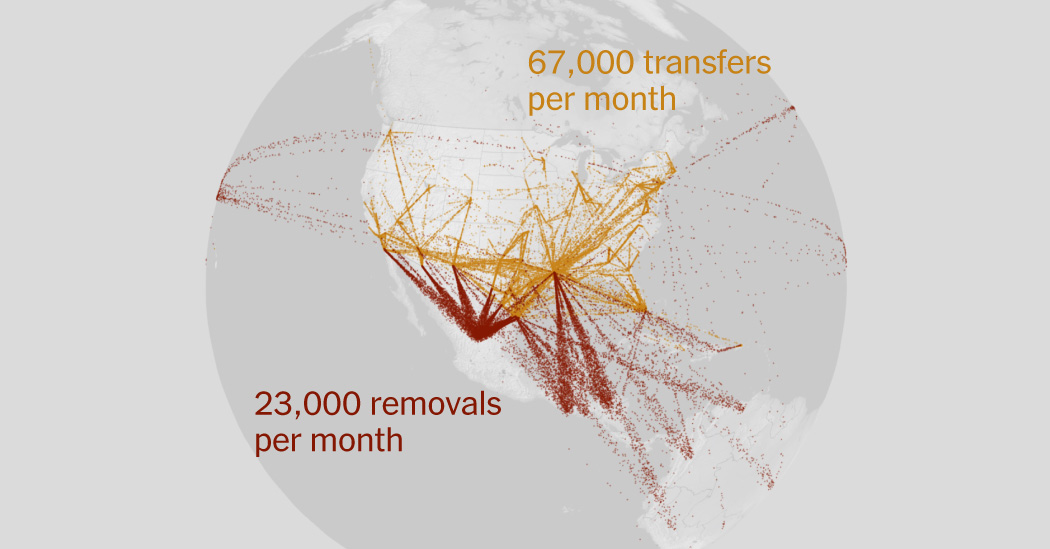

Because detention facilities are concentrated in the South, people arrested elsewhere are often quickly transferred long distances to places where there is space, often in Texas and Louisiana, far from family and lawyers.

Each line here represents the average monthly volume of transfers of immigrant detainees between detention facilities. Darker lines reflect higher numbers of detainee transfers.

People are moving around the system more than last year — passing through an average of three different facilities over seven weeks before they are deported. Immigration lawyers say the process has caused some people to give up their asylum cases and to agree to be deported.

Where deported people go

The Trump administration has deported people to almost every country in the world, including those that had resisted taking back their citizens. It has sent people to repressive regimes, including Afghanistan, Iran and Russia, and it has pressed countries like South Sudan and Uganda to accept deportees from far-away places who have no ties to those countries.

Detailed data on ICE removals was available only through the end of July, but it showed that the monthly pace of deportations had more than doubled compared with last year for people from more than 100 places.

China, India, Russia, Panama, Turkey and Vietnam were among the countries with the largest increases. The pace of deportations to the Northern Triangle of Central America has actually slowed somewhat because fewer people from those countries are crossing the border.

An analysis of less detailed data on deportations shows that their pace accelerated after July; as of December, ICE is on track to deport about 390,000 people in Mr. Trump’s first year.

The Trump administration has redrawn the map of immigration enforcement. Under pressure to expand further — and mounting backlash from the public — these patterns may change again.

About the data

The data comes from Immigration and Customs Enforcement and was obtained by the Deportation Data Project through a public records lawsuit. It covers every arrest, detention stay and deportation conducted by ICE through Oct. 15, 2025, for arrests and detentions, and through July 28, 2025, for deportations.

To analyze how people moved from arrest to detention to deportation, we combined the data using anonymized, person-specific identifiers in the data and processed it to remove duplicates. In some cases, we removed rows with missing fields.

For the animated maps, each dot shows one person per month traveling between detention facilities, ports of departure and destination countries. Routes with fewer than five average people per month are not shown. The numbers of removals and transfers shown are for the period from Jan. 20 to July 28, 2025, normalized to a 30-day monthly average.

We identified the locations of detention facilities through a combination of addresses from ICE’s biweekly detention management report, a public records request filed by The Times, and data published by the Vera Institute of Justice and The Marshall Project.

We categorized arrests “while in custody” to be those with an apprehension method listed as “CAP Incarceration” or “Custodial Arrest.” All other arrests conducted by ICE were categorized as “from the community,” except those with a final program listed as Border Patrol. Those arrests and detention book-ins with a final program of Border Patrol and no corresponding ICE arrest were categorized as “border arrests.”

👇Follow more 👇

👉 bdphone.com

👉 ultractivation.com

👉 trainingreferral.com

👉 shaplafood.com

👉 bangladeshi.help

👉 www.forexdhaka.com

👉 uncommunication.com

👉 ultra-sim.com

👉 forexdhaka.com

👉 ultrafxfund.com

👉 bdphoneonline.com

👉 dailyadvice.us