Louisiana has been warned of soaring toxic gas levels that can “directly damage DNA.”

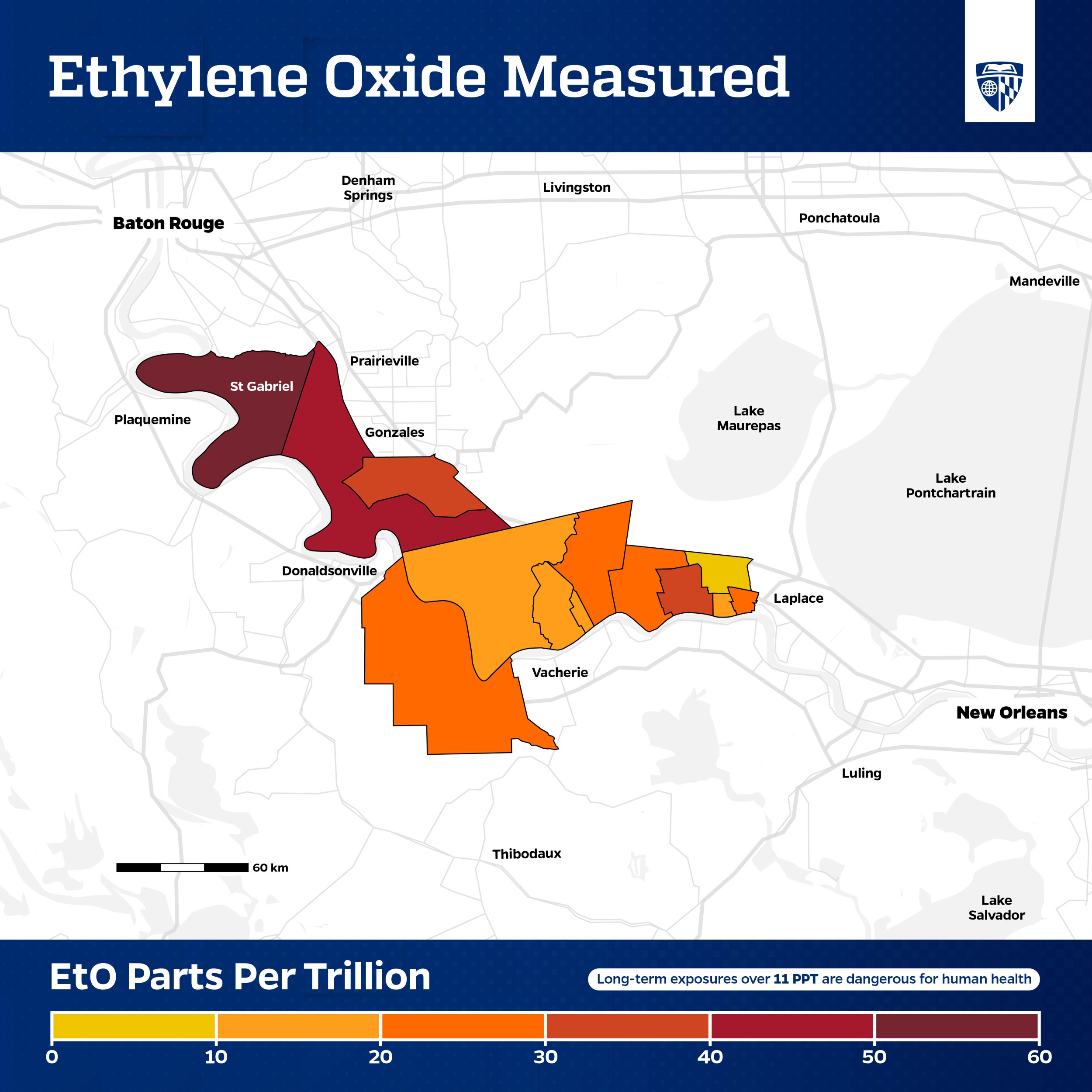

A recent study revealed that toxic levels of ethylene oxide gas were found in parts of Louisiana, at concentrations thousands of times higher than what is deemed safe.

The discovery was made using an advanced mobile air-testing lab, which detected much higher levels of the gas than previously estimated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The study was conducted by environmental engineers from Johns Hopkins University, and indicates a significantly higher risk of cancer for people living near facilities that manufacture and use ethylene oxide.

“Our findings have really important implications for community residents, especially infants and children,” Keeve Nachman, associate professor of environmental health and engineering, said in a statement. “Ethylene oxide has been shown to directly damage DNA, meaning that exposures that occur in early life are more dangerous.”

Newsweek has contacted the EPA and the Louisiana Department of Health by email outside regular office hours.

Khamar Hopkins/Johns Hopkins University

Ethylene oxide is a human-made gas often used to produce other chemicals, fumigate, and sterilize medical and food production equipment. Even at low concentrations, it is highly dangerous to humans, with long-term exposure linked to cancer. Inhalation is the primary route of exposure, which is particularly concerning for people living near or working in facilities that handle the gas.

“I don’t think there’s any census tract in the area that wasn’t at higher risk for cancer than we would deem acceptable,” Peter DeCarlo, an associate professor of environmental health and engineering said in a statement. “We expected to see ethylene oxide in this area. But we didn’t expect the levels that we saw, and they certainly were much, much higher than EPA’s estimated levels.”

Detecting ethylene oxide in the air is challenging with traditional monitoring methods.

“There is just no available data, no actual measurements of ethylene oxide in air, to inform workers and people who live nearby what their actual risk is based on their exposure to this chemical,” DeCarlo said.

To address this issue, the researchers developed a mobile lab capable of measuring ethylene oxide in real time. The lab, consisting of two vans equipped with sensitive analytical equipment, was used to survey the air in southeastern Louisiana, an area known as “Cancer Alley” due to its history of exposure to toxic chemicals.

“We went out to answer the question: how much ethylene oxide is in the air in this region and are the levels of concern for people’s health?” said lead author Ellis Robinson, an assistant research engineer at Johns Hopkins. The team drove the mobile lab around the area for about a month, collecting air samples along a heavily industrialized route between New Orleans and Baton Rouge.

The testing revealed ethylene oxide levels as high as 40 parts per billion near industrial facilities—more than a thousand times higher than the accepted risk level for lifetime exposure, which starts at 11 parts per trillion. These elevated levels were found not only close to the industrial plants but also as far as 10 kilometers (6 miles) downwind.

The EPA has recently announced stricter regulations for ethylene oxide, requiring facilities to drastically reduce emissions. The findings from this study could help regulators identify areas that need closer monitoring and more stringent controls to protect public health.

This research also highlights the urgent need for better tools and methods to monitor air quality and protect communities from harmful pollutants, according to the study.

“Our study demonstrates the need for more accurate measurements to help identify locations to install monitors for more long-term monitoring and so we can best protect the health of people who are living in those areas,” DeCarlo said.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about ethylene? Let us know via sc*****@******ek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

👇Follow more 👇

👉 bdphone.com

👉 ultraactivation.com

👉 trainingreferral.com

👉 shaplafood.com

👉 bangladeshi.help

👉 www.forexdhaka.com

👉 uncommunication.com

👉 ultra-sim.com

👉 forexdhaka.com

👉 ultrafxfund.com

👉 ultractivation.com

👉 bdphoneonline.com